integers = [1..]Lists are Streams and Iterators

Lists are the most common data structure in Frege (just like in Haskell).

Coming from a Java background, one may expect a number of properties about lists:

-

how much space they take up in memory

-

how they can be accessed

-

how they can be modified

-

what features are available

-

how they can be iterated over

-

how they relate to streams, iterators, sequences, and collections.

Many of these properties are profoundly different in Frege. They are much more versatile and powerful. They can be infinitely large, they can be used as streams, and they replace iterators and sequences.

Memory consumption

Frege lists often use hardly any memory at all. The most obvious example is the infinite list of all positive whole numbers:

Though infinite, the integers list does not exhaust the memory.

Neither do other large lists of that kind:

large = [1..100_000_000]Well, you might think that this special feature only works for range-like lists but thanks to laziness, it is a feature that works for all lists where the individual values are somehow derived:

-- derive next value from predecessor

cardinals = iterate (+1) 1

-- derive by repeating

toggles = cycle [true, false]

-- derive by mapping

data BigData = BigData { number :: Integer }

infiniteBigData = map BigData [1..]It takes some practice for the Java programmer to let go his innate worries about large lists and collective data structures in general.

First: as long as the list is not evaluated, it takes up only as much memory as the piece of logic ("thunk") that defines it. This is almost no space at all.

Second: elements are only created when needed, e.g. asking for the

1000th element of infiniteBigData will only create one

BigData value (not 1000 of them).

Access and modify

It should come at no surprise that you can use the functions below

to get access to elements in the list. Access to a value at a given

index uses the !! operator, which needs an extra import.

import Data.List(!!)head [0..10]

last [0..10]

length [0..10]

[0..10] !! 5

-- pattern match with cases

doWithHead [] = ... -- when empty

doWithHead (head : tail) = ... -- use headYou can see that Frege lists can be used like collections. The collection functions have a catch, though.

Collection-like functions are often better replaced with approaches like pattern matching with case discrimination. Those are always safe.

Lists are immutable

The typical Java way to work with lists is to change them in-place. This is never the case in Frege. Lists are immutable.

Java 8 streams work destructively: calling skip(1) on a stream

will modify the stream and the respective element is lost.

Not so in Frege where the following functions can be called on a

list just like their equivalents on Java streams but return an efficient

"copy" or "view" of the list. The original never changes.

drop 2 [0..10]

take 5 [0..10]

map (+1) [0..10]

filter (<10) [0..10]

fold (+) 0 [0..10]|

Note

|

Efficiency comes from the fact that the original list is immutable and thus

views on a sublist rarely have to copy anything. For example drop 2 only

needs to set the starting point of the view two elements down the tail.

In addition comes laziness such that map (+1) will never be calculated

if the mapped value is never asked for.

|

But lists are not only lazy collections and streams at the same time, they can also be seen as iterators and sequences.

Lists as iterators

Iterators pass each element, one at a time, to a function that uses that element.

for [1..10] println|

Note

|

The for alias for forM_ is available since version 3.22.524.

It has the additional benefit that it works not only on lists but

on any ListSource (those have a toList function).

|

But there is more.

When a list contains actions (values of type IO()), then they become

essentially sequences of these actions with the help of the

sequence function.

actions = map println [1..3]

sequence actionsPutting it all together

Let’s print square numbers by using the techniques from above. To make things a bit more interesting, we will calculate them in a very basic way by pure counting (without multiplication).

The trick is that any square number is a sum of uneven numbers

so we need those first. While there is a built-in facility in

Frege for that purpose ([1,3..]), let’s for the fun of it

create our own stream of uneven numbers.

Starting at number 1, we get the next uneven number by adding 2 to the previous one.

unevens = iterate (+2) 1Now, to get the n'th square number, we need to add up the first n uneven numbers by folding them with the plus function.

square n = fold (+) 0 $ take n unevens|

Note

|

Using the sum function would have been shorter but less interesting.

|

Using the square function (that works on the stream of unevens) we can now create a stream of all squares by mapping the stream of all whole numbers to their squares.

squares = map square [1..]For printing the squares, we could just evaluate them in the shell, which does the printing for us. Otherwise, we can use the squares themselves as the iterator that we need for printing. Printing an infinite stream is not a good idea, though, and therefore we limit the iteration to any slice that we are interested in.

for (take 10 $ drop 100 squares) printlnA closing example

Thinking of Frege lists not only in terms of a collection but also as streams, iterators, and sequences first takes a bit to get used to. It is needed, though, to harness their full power.

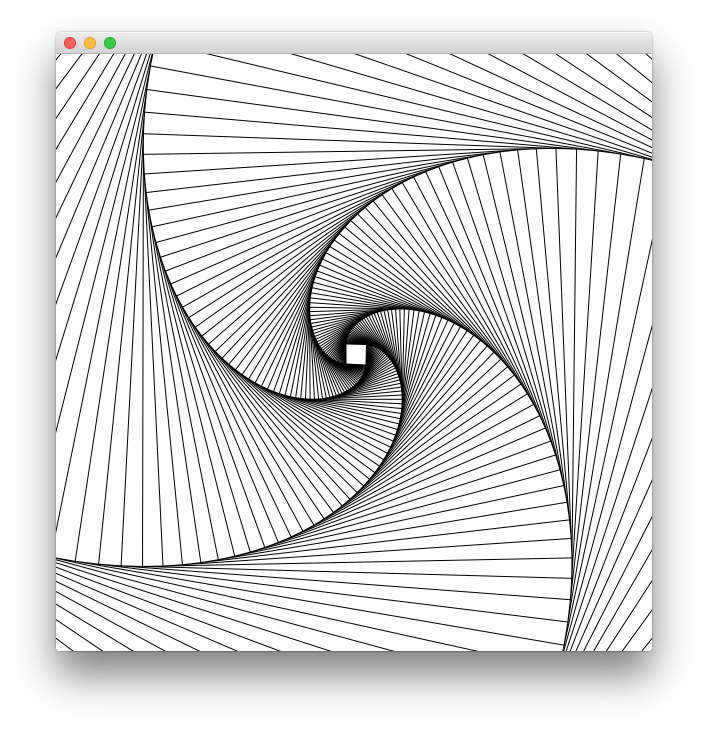

The other day, I was trying to let Frege paint some paper doodle. It is about connecting points and edges such that you get the illusion of a never-ending staircase.

Given a starting point and the logic how to calculate the next step, the code is literally (!)

stairs = iterate step startThe doodle itself needs a graphics context for drawing (and thus the FregeFX REPL) and the doodling itself is just the sequence of connecting the calculated steps:

doodle ctx = map (connect ctx) stairsNote that up to this point, we are still purely functional! We have merely created an infinite list/stream/iteration of actions.

The effective painting is then done by limiting the sequence to a useful slice and passing it for

execution to the paint function: paint (sequence_ . take 500 . doodle).

It was this very example that made me appreciate the versatility of lists. It allows separating the specification of what to do from executing that specification. My first reaction was: "But that may lead to large, memory-consuming lists!" and it took me a bit to understand why this is not the case.

References

| The FregeFX REPL |

https://github.com/Dierk/frepl-gui |

| Code of stairs doodle |